Additional information

| Weight | 800 g |

|---|---|

| Authors | |

| Pages | 188 |

| ISBN | 906299332X, 9789062993321 |

| Publication Year | 2024 |

| Publisher |

€24,50 excl. VAT

Also available as ebook on eBooks.com.

One of the greatest pleasures and privileges I had in my time at Yale Eye Center was the opportunity to invite and host distinguished guest speakers. Our department held weekly Grand Rounds, which often featured young, rising stars in ophthalmology. But it was at our several annual meetings, scattered throughout the year, that we were able to recruit the world-class superstars of our profession. Some were friends whom I had met at meetings or served with on committees, and others were well-known names with whom I looked forward to establishing a friendship. But of all the prominent speakers we hosted at Yale, the one whose visits will forever stand out in my mind is Dr. Alfredo Sadun.

I cannot say for certain when Alfredo and I first met. It was probably during one of the committees we served on together. But I had been aware of his international reputation long before we became friends and was thrilled when he accepted my invitation to speak at Yale. As it turned out, he had a bit of an ulterior motive for coming to Yale. He was, at that time, program director for his Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Southern California and he was hoping to recruit from among our Yale medical students for his department’s residency program. We arranged for him to meet with our students, and his interactions with them must have been productive, because he agreed to come back the following year. And that led to what became a highly anticipated annual event.

Alfredo Sadun can best be described as a Renaissance man. His chosen subspecialty of neuro-ophthalmology is probably the most cerebral area of ophthalmology, and Alfredo is among the brightest of the bright in that discipline. Academic medicine has three classical missions – research, education and clinical care – and Alfredo has received major awards in all three areas. He has published more than 400 scientific articles in peer-reviewed journals, written chapters in over 80 medical books and co-authored or edited five books. His research has been continually funded by the National Institutes of Health for over a quarter century and has led to five patents.

But the depth and breadth of Alfredo’s knowledge extends far beyond the entire field of ophthalmology and medicine in general. During his annual visits to Yale, I enjoyed hosting him at our Thursday evening dinners for the Fellows of Jonathan Edwards College, one of the residential colleges at Yale. The membership of the college represents professors from all walks of academia, and I was always impressed and amused by how Alfredo could enter into erudite conversations with any of them in their areas of expertise.

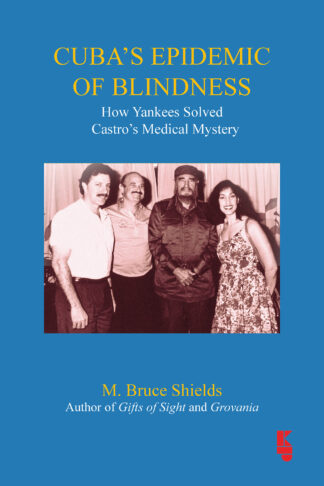

Of course, the highlights of Alfredo’s annual visits to Yale were his lectures, which were highly regarded by our faculty and community physicians. The talks always reflected his thoughtful approach to scientific questions – they were clever, unique and stimulating. But there was one talk in particular that I suspect most who heard it will never forget – Cuba’s epidemic of blindness. In that lecture, he told the amazing story of an epidemic of blindness and other neurological disorders that began in Cuba soon after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and eventually affected nearly 50,000 Cubans. My first thought was, Why have I never heard of this? I knew of the collapse of the Soviet Union but was only vaguely aware of the impact it had on Cuba, which was thrown into an economic crisis and a severe famine, primarily as a result of losing Soviet support. It was around this same time that the mysterious epidemic of blindness began to sweep across the entire island. Fidel Castro threw all his resources into the problem, and yet over a year of research by nearly one thousand Cuban doctors and scientists failed to reveal the cause of the epidemic. Until, that is, a small group of American investigators came to Cuba at Castro’s invitation.

Not long after Alfredo’s Cuban lecture, I was surprised to learn that my friend, Dr. Jim Martone, had been part of the team that went to Cuba with him. I have known Jim since 1985, when he began a glaucoma fellowship at Duke University. We bonded during our time together at Duke and were pleased when our paths crossed again a decade later at the Yale Eye Center. After years as medical director for the international outreach program, Project Orbis, he joined a private group practice in the New Haven area and received a part-time faculty appointment in our department. Eventually, Jim joined the full-time faculty at Yale and became director of their International Ophthalmology program, continuing his passion for world health. But back in the days when he and I were together at Yale, I do not recall him ever mentioning the Cuban epidemic before I heard Alfredo’s talk. That is typical of Jim’s modesty. In any case, when I learned about this amazing story of medical intrigue and ingenious problem solving, and that two good friends were key parts of it, I couldn’t help thinking, This is a story which needs to be told!

Over the next several years, I looked for a way to have the story made into a book. I had another friend in Connecticut, a best-selling author, whom I thought would be ideal to write the book. I arranged for him to meet with Alfredo but, for whatever reason, nothing ever came of that. A few years ago, my author friend died, and I despaired that the story would ever find its way into book form. But then I retired and, having written textbooks and other scientific material in my career, I tried my hand at nonscientific writing and published a couple of books. One day, Alfredo and I were talking, and I said that I would be willing to try making his story into a book, if he wished. He accepted my offer and, for the last two years, I have been working on it with the invaluable help of both Alfredo and Jim.

This is a true story, and I have done my best to adhere to the facts as I have learned them from Alfredo, Jim and other sources. However, I have created characters and events in the first three chapters and in the final chapter to depict what life may have been like for many Cubans and other individuals leading up to the epidemic and in its aftermath. The remaining chapters are based on factual people and events, although I have altered the chronology in places to hopefully enhance the flow of the story line. And the dialogue throughout the book is either from the memory of those who were there or has been imagined by the author, hopefully remaining true to the essence of the story.

In writing this book, I have envisioned a rather broad readership. I anticipate that it will be of interest to ophthalmologists and neurologists and anyone in the medical profession, especially those with an interest in medical history. But it is such a good yarn that I suspect it will also be of interest to many people without a medical background. With the latter in mind, I have attempted to explain some of the more technical aspects of the story, hopefully without boring those for whom the information is common knowledge.

The story truly is amazing in both the scope of the tragic and mysterious epidemic and in the resourceful scientific approach that Alfredo and his team took in solving the problem, when a thousand Cuban scientists were struggling to do so. As such, I believe it deserves to be recorded in the chronicles of medical history, and I am grateful to Alfredo and Jim for trusting me to tell their story. I only hope that the telling is worthy of their remarkable accomplishment.

Bruce Shields

| Weight | 800 g |

|---|---|

| Authors | |

| Pages | 188 |

| ISBN | 906299332X, 9789062993321 |

| Publication Year | 2024 |

| Publisher |